Long Road to Happiness: Malaysia’s Harsh Citizenship Laws Against Multinational Families

SUARA MANDIRI Issue #3

Reeling from International Women’s Day on March 8, a myriad of virtual events and initiatives were held in tow. Despite the raging pandemic, the celebrations were nothing short of noteworthy this year, apart from the absence of the annual Women’s March. The impetus of the century-old occasion is not just to commemorate social, economic, cultural, and political achievements of women, but to lobby for accelerated gender parity.

Undeniably, Malaysia has come a long way since the coalescence of women’s organisations around the issue of Violence Against Women (VAW) in the 1980s, but the struggle for women to attain inherent rights persists. One bone of contention impeding progress in achieving gender equality in Malaysia - citizenship laws.

Grist to the mill of arguments, the citizenship laws have long been an uphill battle for the mothers in multinational families, be it Malaysian mothers with foreign spouses or non-Malaysian mothers with Malaysian spouses. On the frontline of addressing the plight of mothers of multinational families is Family Frontiers, a non-governmental organisation.

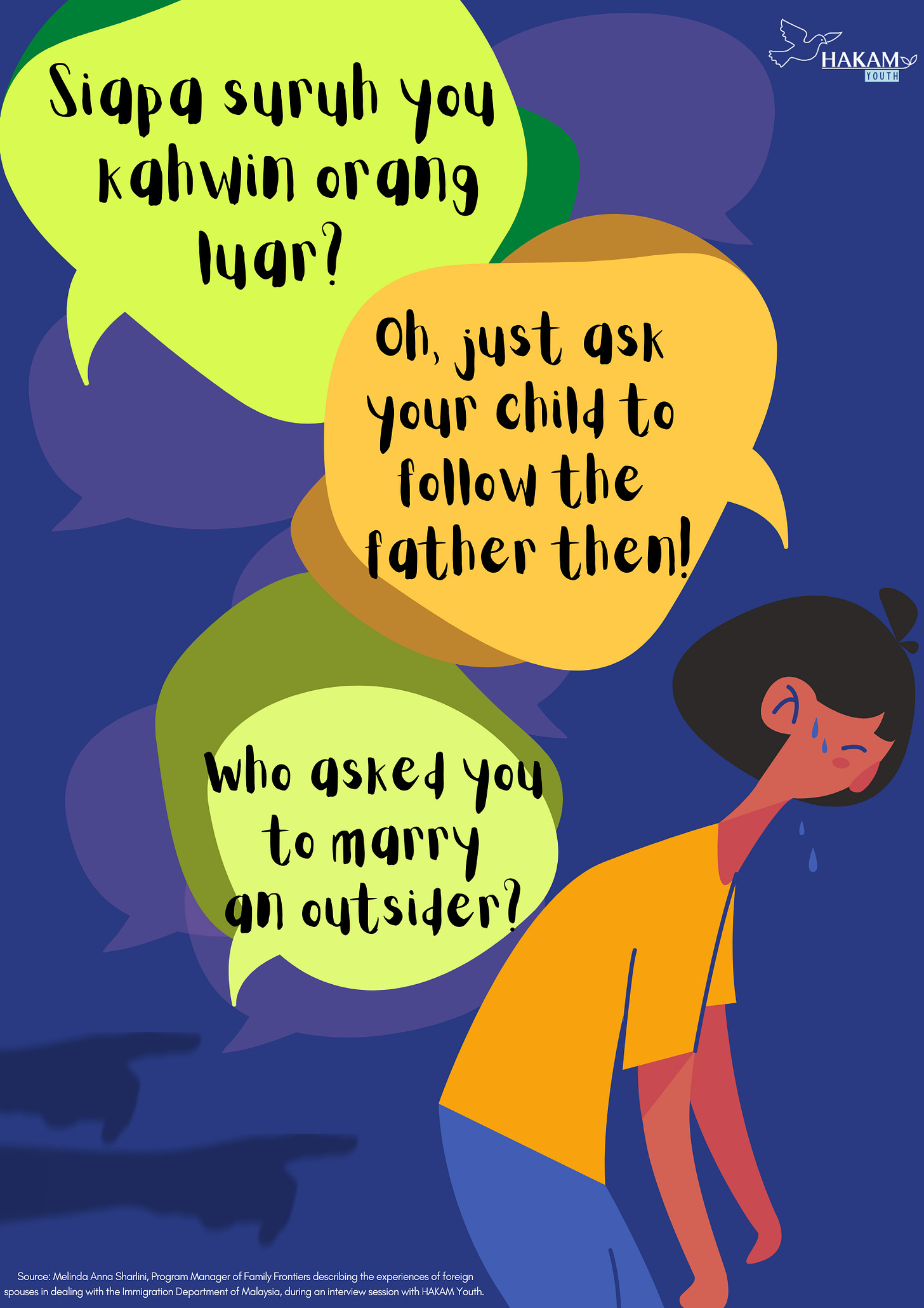

So a lot of the time it feels as though they(immigration)’re punishing them(Malaysian spouse) because they’ve married someone outside of Malaysia. They say stuff like:

HAKAM Youth interviewed the key persons behind Family Frontiers, Bina Ramanand, the co-founder, and Melinda Anne Sharlini, the programme manager, to unravel the intricacies and implications of the citizenship laws in Malaysia and hear their aspirations of eliminating the systemic inequalities suffered by women and multinational families.

The story of Family Frontiers began with Bina, a foreign spouse. Having faced trials and tribulations stemming from the citizenship laws herself, she started penning and narrating her story everywhere she went. Thereupon, she encountered numerous women undergoing similar predicaments, motivating her to co-found Foreign Spouses Support Group (FSSG) with Asha Lim. Family Frontiers was founded in 2009 to advocate for gender equality, citizenship rights, and the rights of multinational families in Malaysia.

In December 2020, Family Frontiers and six women filed a suit at the High Court, seeking a declaration that the citizenship laws contained within the Federal Constitution is in violation of the constitutional protection of equal treatment of citizens by allowing only fathers to obtain citizenship for children born outside Malaysia.[1]

This article, in collaboration with Family Frontiers, aims to dissect the systemic discrimination women face under our current citizenship laws.

Living in Limbo: Unequal Jus Sanguinis

It is a woman who bears the child. Look at the amount of trouble you’re putting her into! She has to risk her life to come into this country just to deliver a child! If it were a man, the child would get citizenship within, like, three days, as some of the men said. A Malaysian man is able to get citizenship of his child borne by a non-Malaysian wife abroad within, the shortest timespan was three days and longest was three months, as reported by some Malaysian fathers. A Malaysian man does not face the danger of travelling whilst pregnant, putting both lives in danger to secure a citizenship for his child. It’s a Malaysian woman in order to secure citizenship of her child has to put her life and yet her life and the yet to be born child’s life in danger to travel to the country! Some of them do not have the luxury to travel, more so during COVID-19 because borders were closed. The situation was very alarming.

- Bina Ramanand, Co-founder of Family Frontiers

According to Article 14 of the Federal Constitution, a father can confer his nationality to his children, regardless of where the children are born.[2] The process is fast and easy, sometimes taking only three days to be completed, as mentioned by Bina. On the other hand, children with Malaysian mothers and foreign fathers have no options, but to resort to obtaining citizenship by application, which is discretionary, according to Article 15 of the Federal Constitution.[3] Family Frontiers had also provided support for numerous families in their application of citizenship for their children. Sadly, the process can take years to complete, and the approval rates are less than 5%. On top of that, no reasons are provided for rejections.

As the agony of waiting and re-applications consume whole families, the children are left vulnerable without access to public health, education, and manifold deprivations of basic human rights due to the lack of a nationality.

In terms of healthcare, as these children are deemed to be stateless, they end up being categorised as foreigners and are compelled to pay exorbitant prices.

In terms of healthcare, these children cannot access public health care in the same way as citizens. They actually have to pay a higher rate, as foreigners instead. Most of the time, it ends up being much more expensive than private hospitals… It becomes very difficult for those that require long term treatment, or those for instance, who require therapy, for like those with disabilities. We have a mother whose child has no development, so she would have to send the child to speech therapy and things like that and we are going to pay really high charges to the public hospital.

- Melinda Anne Sharlini, Programme Manager of Family Frontiers

Apart from costly medical fees, these children also miss out on government-sponsored immunisation programs, dental care programs, and other healthcare programs in schools. Being constantly discriminated against not only prevents the children from receiving adequate healthcare and health education, but also negatively impacts the mental health of the children.

As for education, despite the Zero Reject policy’s aim in ensuring that children receive access to education regardless of their nationality, the application for enrolment is far from simple – it involves a tedious bureaucratic process that consumes time and money.

It is like a chicken and egg system that’s going on. The children cannot get their student visas because they don’t have insurance, and they cannot get insurance unless they have their visas!

- Bina Ramanand, Co-founder of Family Frontiers

The parents have to work hard to persuade either the school or the insurance company to cooperate so their children can be admitted to the school. These complex administrative procedures may take up to three or four months, causing the child to miss out on education. To make matters worse, these children are placed into the same predicament every year, as they must renew their admissions on annually.

Once admitted by the school, non-Malaysian children from low-income families face further problems, as they struggle to pay for their tuition fees, student visas, and textbooks. While Malaysian students can attend government schools for free and receive textbooks through the Textbook Loan Scheme (Skim Pinjaman Buku Teks), it is impossible for these non-Malaysian children. Some may be forced to drop out of school altogether because their parents simply cannot afford the expenses.

In light of these issues, raising a non-citizen child is very difficult in Malaysia. As such, some Malaysian women would rather opt to stay in their husband’s country, the country the child was born in, or a country that is more accepting of foreigners. Further complications may arise if the multinational couple files for divorce: Malaysian mothers may be forced to be torn asunder from their children if they return to Malaysia. This is because countries that adopted the Hague Convention such as the United States and Singapore, require both parents’ permission for a child to move overseas, even if they are divorced. Furthermore, the mother may also be reluctant to bring her children back to Malaysia, due to the lack of protection of her children’s rights. This puts Malaysian women in a precarious position as they might go so far as to remain with their spouses overseas even if they are abusive, out of fear of being separated from their children.

This issue is further exacerbated by the Covid-19 global pandemic, when countries across the world have sealed off their borders and entered lockdowns. In fact, domestic violence has increased during these lockdowns.[4][5]Yet Malaysian women facing domestic violence would find it difficult to leave their abusers because they cannot bring their non-citizen children with them to Malaysia, having sealed its borders against foreigners. Tedious paperwork and negotiations with the Immigration Department will be required for approval to bring her non-Malaysian children into the country, even though the mother is a citizen.

We had a mother in Italy who could not return with a non-citizen daughter to Malaysia. She had refused, “After I’ve come back to Malaysia, they will give her a one-month visa. After one month, they will just ask her to leave the country. What am I going to do?” … “If I have the assurance that my daughter can at least get a PR in my country, then I’m coming back”. In the wake of a failing marriage, a Malaysian woman is left stranded in Italy with her daughter as the Covid-19 pandemic wreaks havoc across the globe. She decided to stay in Italy with her daughter, rather than come back to Malaysia, as her daughter would be safer in Italy.

- Melinda Anne Sharlini, Programme Manager of Family Frontiers

The constitution which ought to protect the rights of citizens had, instead, infringed upon the rights of Malaysian women and their non-citizen children. As Melinda puts it, “Malaysia’s citizenship laws have failed Malaysian women and their offspring.”

In essence, the Malaysian citizenship laws in Malaysia and as set forth in the Federal Constitution, is rather astonishing and perplexing – they directly contradict Article 8, which calls for elimination of gender discrimination.

Federal Constitution, Part III

Article 8: Equality

(1) All persons are equal before the law and entitled to equal protection of the law.

(2) Except as expressly authorised by the Constitution, there shall be no discrimination against citizens on the ground only of religion, race, descent, place of birth or gender in any law or in the appointment to any office or employment under a public authority or in the administration of any law relating to the acquisition, holding or disposition of property or the establishing or carrying on of any trade, business, profession, vocation, or employment.

Following the ratification of the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in 1995, Malaysia has a legal obligation to take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women, and advance gender equality. Malaysia retains a reservation on Article 9(2) of CEDAW: “State parties shall grant women equal rights with men with respect to the nationality of their children”. Sexism and xenophobia remain ingrained in the system. It was only a decade after the ratification of CEDAW that Article 8 was amended to include gender discrimination. Apart from Article 8, there have been no amendments to the Federal Constitution with regards to gender inclusivity, despite the existence of axiomatic gender discriminatory laws such as Article 14.

Diaspora Blues: The Plight of Foreign Spouses

The effects of gender inequality in citizenship laws extends beyond Malaysian women to foreign spouses in Malaysia. The old patriarchal belief that women belong to their husbands causes some to think that only women marry into their husbands’ countries. Because of that, our citizenship laws are keen on stripping the foreign spouses of their autonomy –women should just stay at home. Apart from sexism, xenophobia also has a play in making things difficult for foreign spouses. The systematic discrimination against foreign spouses have caused great grievances amongst multinational families in Malaysia.

My daughter had an asthma attack, but I could not admit her to the hospital, because I was a foreigner, and by that logic my daughter may also be a foreigner. I didn’t have my daughter’s birth cert with me. I had to call my husband to come and admit her to the hospital. She was beginning to turn blue.

- Bina Ramanand, Co-founder of Family Frontiers

Those were the heart-wrenching words of a mother, helpless as her daughter faced mortal danger. Foreigners’ access to healthcare is limited and costly. As long as these foreign spouses remain on visiting visas, their rights are greatly limited. Yet, Malaysia’s Permanent Resident (PR) status is notoriously difficult to gain, throwing foreign spouses and their families into a difficult conundrum as they fight for their rights to live in Malaysia.

Once a foreigner marries a Malaysian, s/he[1] faces a major bureaucratic hurdle – the Long-Term Social Visit Pass (LTSVP). An LTSVP allows a foreign spouse to stay in Malaysia temporarily, with the duration for stay varying between six months and five years.[6] Foreign spouses must reside in Malaysia for at least three years on a valid long-term pass to be able to apply for PR.[7] Sounds simple, right? Not so much.

First off, during the three years before they are eligible to apply for PR (the period of which could range from anywhere from 3 years to 7 years), while on LTSVP, the foreign spouse cannot leave the country.

For five years, I was told I cannot go back to my home country. After three years, I gave up because I was missing home terribly and had post-partum complications.

- Bina Ramanand, Co-founder of Family Frontiers

Bina was told that she cannot leave Malaysia for five years if she wanted to be eligible for PR. Foreign spouses who tried to apply for PR like Bina were forced to be separated from their family in their home country for years, – it is simply inhumane for the Immigration Department to do so. It does not help that much of the information regarding PR is not published and therefore spouses are left to the interpretation of policy by the Immigration Department officers.

Secondly, a foreign spouse can be kept waiting for months before receiving a LTSVP, as the visa does not have a set time frame for approval.[8] During the waiting period, s/he would have to frequently leave the country for visa runs, incurring unnecessary expenses.[9] To make matters worse, newlyweds or childless couples are usually issued with an LTSVP valid for only six months.[10] Low-income families may not be able to afford the constant renewal of visas at all. One would believe that bi-national families live under constant fear of their families being torn apart from complications pertaining to the visa.

I had to be on a dependent pass for me to apply for PR. However, since I went on a work permit, I became ineligible. Yet, no one told me. When I went, they didn’t tell us anything and we had to manage it with children and work.

- Bina Ramanand, Co-founder of Family Frontiers

While on the LTSVP, its holder faces multiple restrictions – s/he cannot receive education, work, open an individual bank account[11], cannot buy affordable housing, and many more.[12] One might wonder “Don’t immigration laws allow LTSVP holders to work?”.[13] Unfortunately, the LTSVP comes printed with the sentence “any form of employment is strictly prohibited – SPOUSE OF A MALAYSIAN CITIZEN”[14], effectively deterring potential employers.[15] Even if the foreign spouse manages to find a willing employer, the process for the endorsement of work is a major bureaucratic hurdle.[16] S/he is also unable to take on professional jobs requiring licensing, such as lawyers and bankers, as they require a PR status.[17] While s/he may choose to apply for an Employment Pass instead, as the interviewee did, s/he would become ineligible for PR status. This makes foreign spouses particularly vulnerable to workplace exploitation, as they may choose to work in informal sectors instead.[18] Families may become trapped in poverty as their sources of income have been limited, or they may be separated because the foreign spouse must work overseas. Foreign spouses economically dependent on their spouses are also vulnerable to domestic violence, as they do not have the economic autonomy or financial capacity to leave.

I was also getting worried, if anything happened to my husband, what is going to happen to my legal status in this country? While I was making my application [for PR], I thought I would help a few other women down the road…

- Bina Ramanand on how she founded the FSSG.

The arduous nature of the LTSVP bares itself at the requirement for the Malaysian spouse to be present every time the foreign spouse needs to settle matters at the immigration department, including visa renewal, work endorsement, application for PR, et cetera.[19] If the Malaysian spouse refuses to be present, the foreign spouse’s immigration status would be at risk.[20] A foreign spouse may also have their LTSVP revoked by the Malaysian spouse, without prior notice, even if they have a valid marriage.[21] This stands even if they have children, and the foreign parent would be separated from them because s/he must leave the country.[22] Separating children and their parents is cruel, inhumane, and impermissible. At times, the foreign spouse is sent back to his/her home country without any access to justice.[23] Our harsh immigration policies and practices make foreign spouses, especially women,[24] particularly vulnerable to domestic violence. It is difficult for them to leave their abusers for fear of being separated from their children as well as the lack of financial and social support to leave. Children may also be trapped with the abusive parent because the foreign parent is unable to leave or bring their children with them when leaving.

Foreign spouses in Malaysia came here hoping to set up a permanent home with their loved ones. Yet Malaysia’s citizenship laws and immigration policies and practices, deeply ingrained with xenophobia and sexism, had all but made life difficult for them and their family. Much needs to be done to address the inequalities faced by foreign spouses in Malaysia. As a first step, perhaps the application process of the LTSVP should be simplified, clarified, and standardised. Foreign spouses should also have the right to work, purchase affordable housing, access affordable healthcare, and other basic rights that are needed to encourage a life with freedom, dignity, and happiness.

Who Holds the Ace Card?

Would the notion of gender equality only remain within spheres of benign discourse? The persistence of these anachronistic citizenship laws is not only detrimental to both women and children in Malaysia, it makes a mockery of the country’s ratification of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).

With the tussle and turmoil of politics and power play, a complete eradication of gender discrimination may not be possible anytime soon. Nevertheless, policymakers should be empowered to address and ameliorate the grievances faced by these distraught families. In the words of Bina and Melinda, “there is no place for gender unequal laws today”. Through their unyielding advocacy for the constitutional reform of our citizenship laws, hope lives on.

References:

[1] FMT Reporters (2020) Six women sue for mothers’ rights to pass on citizenship. Free Malaysia Today. Retrieved: 2021 3 21. URL: https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2020/12/18/six-women-sue-for-mothers-right-to-pass-on-citizenship/

[2] Federal Constitution, Second Schedule, Part II, Article 14: Citizenship by Operation of Law. 1.b) Every person born outside the Federation whose father is at the time of the birth a citizen and either was born in the Federation or is at the time of the birth in the service of the Federation or of a State.

[3] Federal Constitution, Part III, Article 15: Citizenship by Registration. 1. Subject to Article 18, the Federal Government may cause any person under the age of twenty-one years of whose parents one at least is (or was at death) a citizen to be registered as a citizen upon application made to the Federal Government by his parent o/r guardian.

[4] Yap, Lay Sheng (2020 6 9), Enquiries to WAO’s domestic violence hotline spike to over 3 times pre-MCO levels, showing need for preparedness for next round of pandemic, Women’s Aid Organisation. Retrieved: 2021 3 21. URL: https://wao.org.my/enquiries-to-waos-domestic-violence-hotline-spike-to-over-3-times-pre-mco-levels-showing-need-for-preparedness-for-next-round-of-pandemic/

[5] Conolly, Kate (2020 3 28). Lockdowns around the world bring rise in domestic violence, The Guardian. Retrieved: 2021 3 21. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/mar/28/lockdowns-world-rise-domestic-violence

[6] Long Term Social Visit Pass, Official Portal of Immigration Department of Malaysia (Ministry of Home Affairs). Retrieved: 2021 3 19. URL: https://www.imi.gov.my/portal2017/index.php/en/pass.html?id=294

[7] Residence Pass, Official Portal of Immigration Department of Malaysia (Ministry of Home Affairs). Retrieved: 2021 3 19. URL: https://www.imi.gov.my/portal2017/index.php/en/pass.html?id=284

[8] Foreign Spouses Support Group (2019), Submission to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights in advance of the Visit to Malaysia Independent Stake Holder Submission.

[9] Ibid. 8.

[10] Ibid. 8.

[11] Unless they are employed. Ibid. 9.

[12] Ibid. 8.

[13] Ibid. 6.

[14] Foreign Spouses Support Group (2016 4 1) Ease the burden of foreign spouses, The Star. Retrieved: 2021 3 19. URL: https://www.thestar.com.my/opinion/letters/2016/04/01/ease-the-burden-of-foreign-spouses/

[15] Ibid. 8.

[16] Ibid. 8.

[17] Ibid. 8.

[18] Ibid. 8.

[19] Ibid. 8.

[20] Ibid. 8.

[21] Ibid. 8.

[22] Ibid. 8.

[23] Ibid. 8.

[24] “Worldwide, almost one third (27%) of women aged 15-49 years who have been in a relationship report that they have been subjected to some form of physical and/or sexual violence by their intimate partner.” - 2021 3 9. Violence against women, World Health Organization. Retrieved: 2021 3 19. URL: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women